Molly Moore, her husband, Joe, and their four young kids have been traveling in their 2019 30’ Airstream since July 2020, attempting to let go, spend time in wild places, and instill a strong foundation of Leaving No Trace, while picking up the trail of their Legos left at campsites across the entire country. She tells her family’s story at The Moore Air, which recounts their adventures and discoveries from remote parks to big cities, all while growing up and slowing down in tight quarters…together. You can also catch them on instagram @the_moore_air. Read earlier installments here.

“Does anyone know what controls the tides?” our tour guide Meg asked.

“The moon,” my kids (8, 6, 5, and 2 years old at the time) quickly responded.

“Do you know the difference between a grass, a sedge, and a rush?”

“Yes!” as they recited the poem they had learned in the Everglades to help distinguish between the three.

As they continued to be peppered with conversation-starting questions, they continued to answer.

“Do you know why a bird poops as it takes off flying?”

“To weigh less,” they knew.

As the tour continued, they continued to exhibit a vast knowledge of the natural environment that I had never acknowledged was just so vast. They were identifying birds and fish, discussing the animals’ genus and species, and sharing their own knowledge of sea and marsh life, all while listening patiently and attentively, hungry for more knowledge about the natural world around them.

On this fabulous tour with Meg, owner of Botany Bay Ecotours, on Edisto Island, SC – as I watched my kids interact with another adult in this way (the closest thing to a non-parent teacher that they had had in months) – I only then realized what an education they had been getting. I had spent the last seven months recognizing all our learning shortcomings, feeling behind, struggling to convince my kids to do a worksheet, questioning if they were learning what they needed to learn, and altogether assuming I was failing them in my quest to roadschool. I knew I was evolving as a teacher and parent; I had gotten better at letting worksheets go in the name of space, exploration, and flexibility. I also knew my kids were fully alive, doing things that they not only loved, but things that were pushing them – exploring, fishing, making new friends, cooking, drawing up maps, reading. My two-year old could even identify the difference between a heron and an egret.

But was this enough?

And then the Ecotour. My kids were discussing animal mating patterns, environmental issues, and international dark sky places with another adult. They were sharing their knowledge and drinking up another’s, swapping stories, thirsty for whatever was offered. And Meg had much to offer. They learned the differences between univalves and bivalves, bay and sound, adult and juvenile pelicans. They visited and learned about a 4,000-year-old shell midden. They learned how the huge trees along the coast were used for boat building. They heard marsh wrens and learned how they make interesting nests woven into the marsh grasses (or were they sedges?). We learned why the marsh sounds like it’s popping as the tide recedes. We learned how women, in the quest to save birds from being killed so that fashionable hats could don their feathers, founded the Audubon Society. We learned how Harriet Tubman had led the Combahee River Raid, through the waters we were on, rescuing over 700 enslaved people. The kids, rapt with Meg’s stories, did not move a muscle except to turn their necks for the fish jumping, dolphins emerging, or birds taking off in the corner of their eye.

Exploring the St. Helena Sound and hopping out on the uninhabited Otter Island to search for univalves, bivalves (and litter we can throw away).

Only after these three hours with Meg did I fully realize the education my kids were experiencing. They had spent seven months on the road, being exposed to a massive amount of information – new places, new animals, new activities, new surroundings, new cultures, new environments, and a new lifestyle. Some of those things piqued their interest. And because their interests were piqued, their investment in understanding deepened. We were reading books and poems together, out loud: the Burgess Book series, My Family and Other Animals, Nature (and Ocean) Anatomy, and The Lost Words. We were writing postcards, sharing our adventures with friends and family. We were trying new hobbies like pump tracks, tying flies, canyoneering, and snow skiing. We were noting the transition of the jay across the country – when there were magpies, blue jays, Steller's jays, or gray jays (otherwise known as the “camp robber,” what a great nickname).

We were distracted on hikes figuring out if coniferous trees were firs, spruces, or pines. We were mapping our route, learning cardinal directions, geography, history, and weather patterns. We were naming and learning about the indigenous tribes native to the area. And we were applying some new-found flexibility that allowed us to invest where interest abounded. One child asked to learn Latin to better understand animal taxonomy. One child journaled with a goal of writing books to help save animals. Another child learned multiplication to count flower petals in a bouquet of wildflowers. Another painted with watercolors to capture the sunset, then the mountain range. Another would rise early to bird watch, seeking the hardest to find birds native to the area. We knew temperatures because we were outside all day, every day. We knew the phases of the moon because we saw it every day. We knew when the sun would set and when it would rise because it put us to bed and work us up every day.

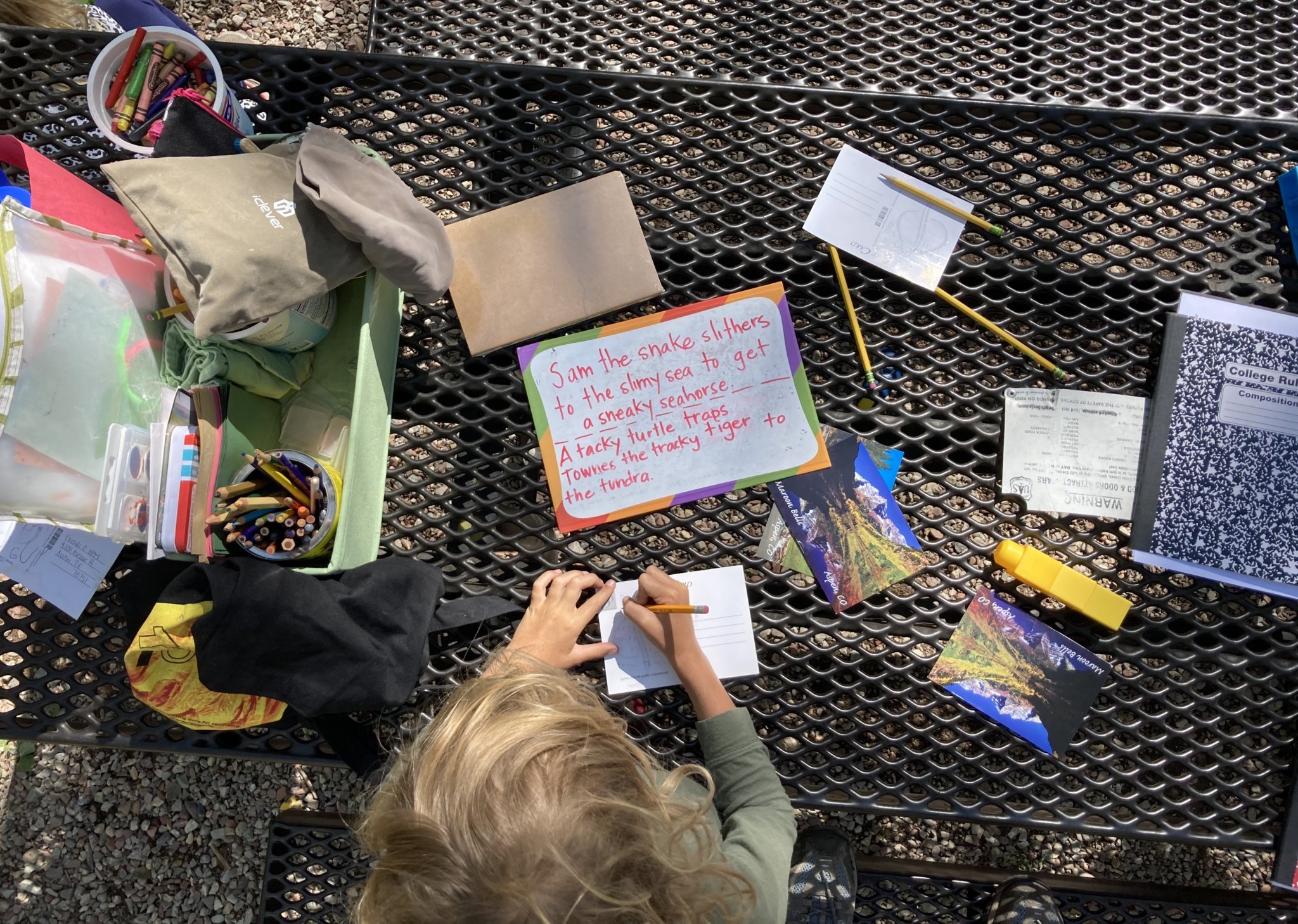

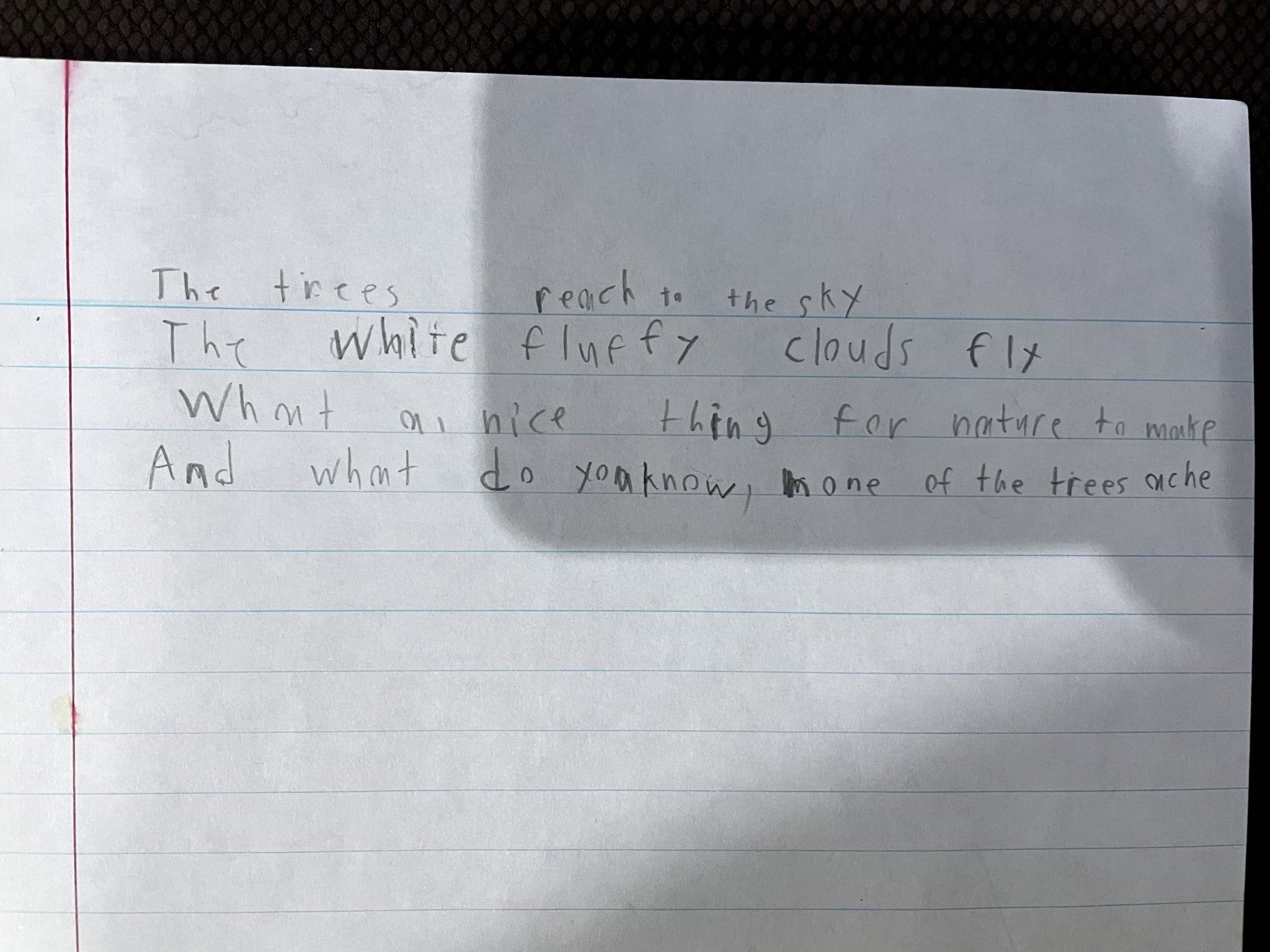

The kids recording the day’s observation in their nature journal, exploring alliteration, attempting to figure out a tree’s age, finding fiddler crabs, and writing poetry.

Yet, set on them “learning,” I didn’t let go of the worksheets. I continued to prioritize phonics. I made sure we were checking boxes along the way. This tension of our learning was best captured when one child was giving a tour of our Airstream to my uncle. He opened our treasure trove of nature books and upon being asked “Oh, are these all your school books?” responded, “Nope, not those.” Even then he could not associate his wealth of knowledge with what he understood to be the process of learning (the workbooks, the curriculum). And it was only after our Ecotour that I, too, began to unravel and disassociate “learning” from the chronological steps of gaining information that I had always known it to be.

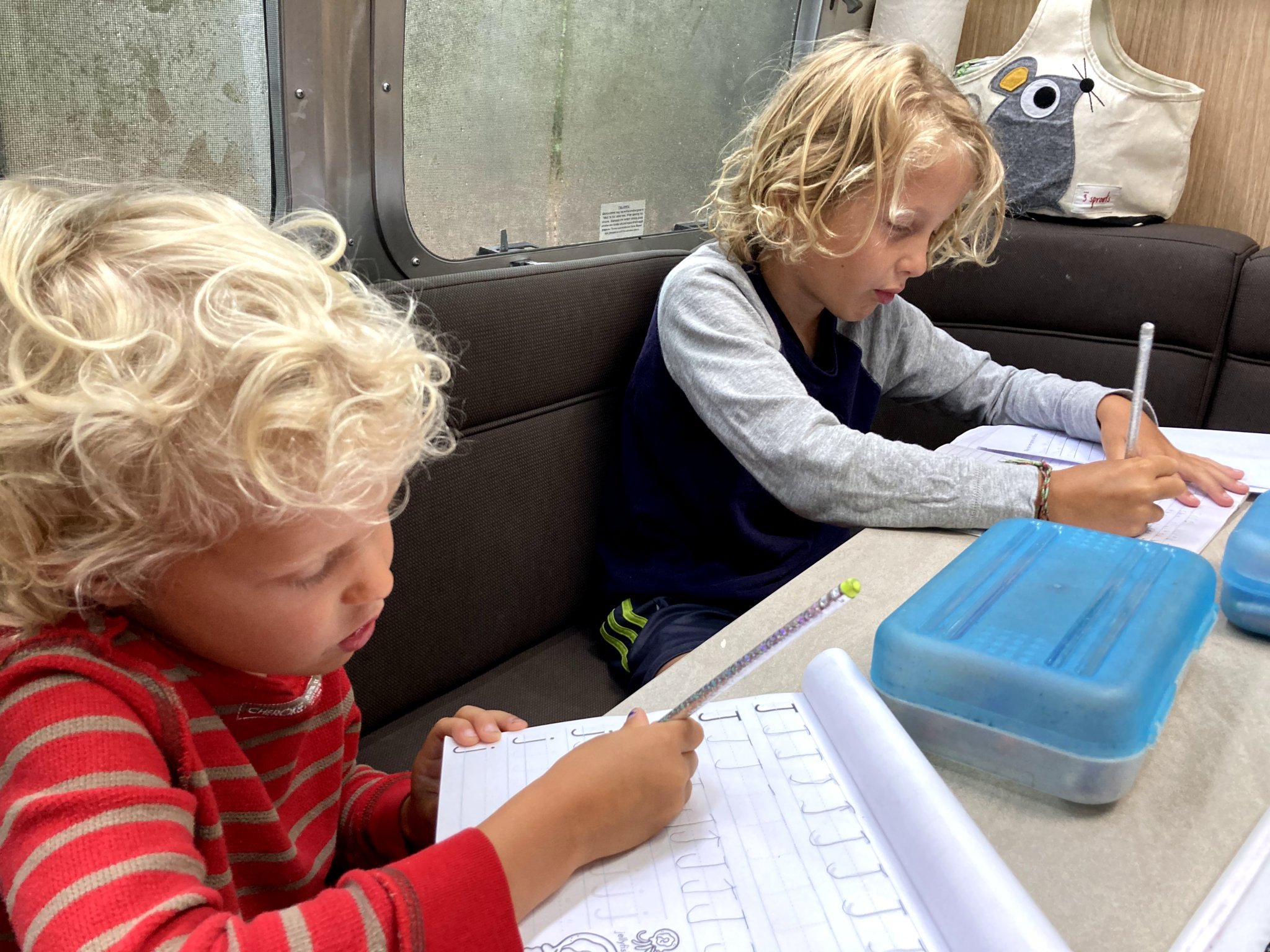

The kids “doing worksheets” amidst a tire change, on a rainy day (inside), on a California beach, on top of a tree stump, overlooking the Pacific Ocean, and overlooking Mount Rainier.

Though I was floundering through the place values, phonics, and the ever-challenging reversal of the “b” and “d,” the children were learning. And not just learning but seeing education as a tool to further explore the things that most captivated them and sparked their curiosity. They were seeing education as way to help them make sense of things. They were more and more driven for tools that would help them explore, help them express, help them know.

Our messy roadschooling in Chrissy has forever upended my notion of education. It has highlighted the importance of giving kids abundant access in order to discover interests, passions, and kindling to ignite their fire. The learning follows.